We asked a class of university students taking Food Microbiology at North Carolina State University to fill out a survey regarding knowledge of Campylobacter. The class was composed of students from the Food Science department (denoted FS) and Microbiology department (MB). There were both undergraduate and graduate students in the course.

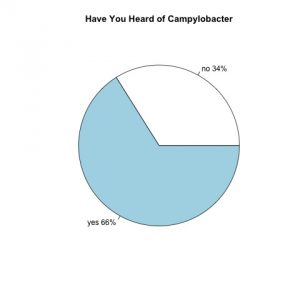

The first question asked the students if they had ever heard of Campylobacter. Of 57 students who participated in the survey, 34% responded “no” and 66% responded “yes”. The data was further divided and Fisher’s Exact tests were performed to see if the class (FS405, FS505, MB405 or MB505), major (Food Science or Microbiology) or rank (undergraduate or graduate) affected the outcome of having heard of this pathogen. There was no statistically significant effect of class on the outcome of whether or not students had heard of Campylobacter (p=0.298). Additionally, there was no effect from major ( food science or microbiology) or status (graduate vs. undergraduate) (p= .750 and .097 respectively).

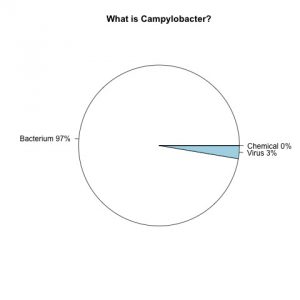

If participants answered yes to the first question, we then asked them if Campylobacter was a virus, a bacterium, or chemical. The vast majority (97%) of participants who had heard of Campylobacter knew that it is a bacterium.

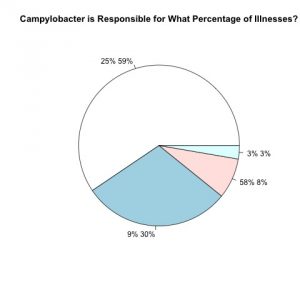

Next, the participants were asked what percentage of foodborne illnesses caused by 31 known pathogens Campylobacter is responsible for? The most commonly reported answer was that Campylobacter is responsible for 25% of foodborne illnesses. The correct answer of 9% was selected by 30% of participants, and no participants selected chemical as a response.

Next, the participants were asked where one might catch Campylobacter. The most common and a correct response (34%) is that Campylobacter is associated with poultry. However, 18% of respondents mistakenly thought that this might include eggs. Unpasteurized milk and dairy products was another common response (23%) and is also a correct answer. No respondents chose a sick friend as a mode of infection, and 18% of respondents chose produce.

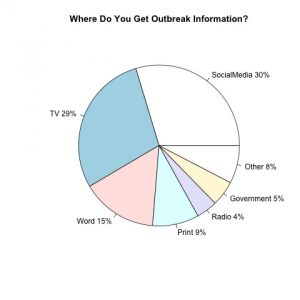

Finally, participants were asked where they get information about foodborne outbreaks. The results were nearly equally split between social media (30%) and TV (29%). Word of mouth was also popular (15%). Print news (9%), radio (4%), government (5%), and other (8%) made up the rest. The “other” category commonly included other websites such as FoodSafetyNews.com which the students wrote in.

It is not surprising that so many of the students taking Food Microbiology have heard of Campylobacter. These students take general microbiology, and might have learned about foodborne pathogens then. Students are over estimating the burden of reported foodborne diseases from Campylobacter in the U.S . They also do not have a clear understanding of the routes of transmission.

This survey was administered at the beginning of the semester. It may help professors identify gaps in students’ knowledge regarding this organism. For example, students should understand that Norovirus and Salmonella are responsible for many more illnesses than Campylobacter. However, the possibility of serious consequences from campylobacteriosis makes this a serious organism to consider. Additionally, since Campylobacter is rarely responsible for large outbreaks, it may not make headlines. Survey participants get much of their news on social media and TV and may miss these reports.