There are many concerns about how the gut microbiota is impacted by antibiotics. Since the widespread use, and sometimes over use of antibiotics began around 80 years ago, bacterial antibiotics has increase worldwide. This makes bacterial infections harder to treat and increases the risk of severe side effects. If was only this year in January that a woman died from a bacterial infection contracted after surgery that was resistant to 23 different antibiotics.

It’s clear that bacterial antibiotic resistance has risen alarmingly. What is less clear is how those antibiotics effect the gut microflora. Studies recently performed have shown that a dysbiosis, an “unbalanced” or abnormal state of the microbiome, in the gut can cause unchecked microbial growth of low abundance organisms known as opportunistic pathogens. These opportunists are usually kept in check by other dominant microbes but when those microbes decrease in number, the opportunists can grow unchecked and cause devastating health issues.

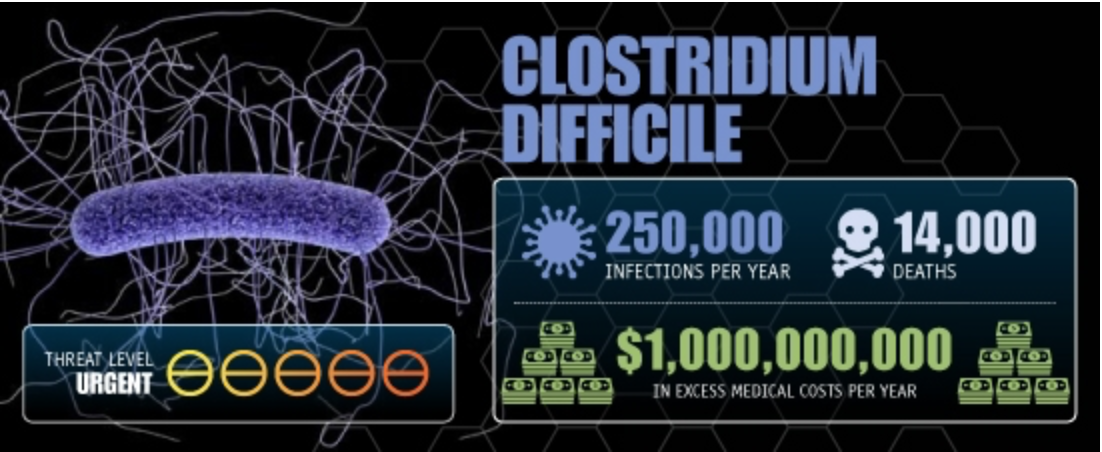

The most recognized of these microbes is Clostridium difficile, or C. diff for short. C. diff can be present in our bodies but not normally at high levels. Infections usually occur in healthy individuals after a broad-spectrum antibiotic has been prescribed to take care of another issue or infection. The antibiotics will take care of the infection but will also decimate some of the normal microbes that are present in the gut and allow C. diff which is often resistant to the antibiotics prescribed to grow and cause a subsequent infection. C. diff can be a large problem with side effects including, diarrhea, pain, colitis (colon inflammation), and even death in serve cases or within immunocompromised populations.

Image credit: CDC Report “Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013”

Even less understood is the effect antibiotics may have on the ability of exogenous pathogens to cause disease through colonization of the gut. A recent paper by ___ et al. investigated this issue in mice. They inoculated 2 groups of mice, one treated with antibiotic prior and one untreated, with either Campylobacter jejuni, a pathogen that can effect formerly healthy hosts, or Acinetobacter baumannii, an opportunistic pathogen that has been known to cause infection in patients housed in intensive care units. This allowed them to determine if antibiotics made the mice more susceptible to those pathogens and how the antibiotics in combination with the pathogens influenced the diversity of the gut microbiota. They found that the pathogens were able to colonize the mouse gut equally well regardless of antibiotic treatment. Antibiotics did cause a decrease in the diversity of gut microbiome. However, some of this diversity was recovered when the mice were inoculated with C. jejuni, which was puzzling. This could be due to C. jejuni competing with dominant microbes, allowing other minor members to flourish.

Regardless, the investigation of another piece of the antibiotic/gut interaction puzzle has begun. More studies will be needed to clarify exactly how antibiotics effect the susceptibility of the gut microbiome to pathogen infection and colonization. It will likely be dependent on the type of antibiotic and microbe but only research will tell. Stay curious and keep researching!

References

CDC. Antibiotic Resistance FAQs. 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community/about/antibiotic-resistance-faqs.html

Johnston, Lance. CDC News. Jan 23 2017. http://www.cdc.news/2017-01-23-us-superbug-kills-woman-infection-resistant-to-26-antibiotics.html

CDC. FAQs for C. diff Patients. 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/organisms/cdiff/cdiff-patient.html

Iizumi T et al. Effect of Antibiotic Pre-Treatment on Pathogen Colonization in Mice. Gut Pathog. Nov 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5116224/?bhn_mid=57755508&bhn_rid=418500335&cmpid=DGMB_WEB_MB_170119_EM_BH_Antibioticresistance_NA