Feedback buzzes through the cramped room lined with fabric walls. The sounds of not-quite quiet shuffling are interspersed with scratch of clearing throats, the rustle of turning program pages, and the hum of lowered chattering voices. Despite the subdued noise- the room is anything but dead. Excitement crackles along the edges of every whisper and movement because the microbiome and metagenomics session is about to start. Welcome to IAFP 2016.

For those who can come, the IAFP annual meeting is a wildly exciting dive into the new, innovative, and well-loved world of food safety. The relatively small conference allows one-on-one interaction with dedicated companies, passionate researchers, and students from all over. The sessions are intensive, the reunions joyful, and the mixers lively. IAFP is conference like no other.

Microbiomes have been around for a while now but it’s only recently that they have been applied to a wide array of areas, including food. MARS and IBM are launching a food microbiome project that aims to characterize the microbiomes of different food products. The FDA implemented GenomeTrakr, which uses whole genome shotgun sequencing (WGS) to aid in outbreak investigations (think whole genome PulseNet). And companies are starting to use microbiomes and metagenomics internally. Considering all of this, it’s no wonder that IAFP placed a marked emphasis on microbiomes, metagenomics, and their role in food safety. For a self-proclaimed metagenomics and microbiome enthusiast (I have occasionally signed off on emails with “Metagenomic Meg”), this created the session list of my dreams.

Notably, a session on how to apply microbiome data and studies to food safety was a highlight for me. The panel on stage answered questions on how this newly accessible technology can be applied to food companies and outbreak investigations. Now that there are so many resources for microbiome studies of the 16S, functional, and WGS varieties, performing these types of studies and analyzing the data obtained is easier than ever. Many of analysis tools are open access and can generate graphs and figures easily. These characteristics make applying this technology possible at both large and small scale operations. There were lots of questions about how to standardize the process of sampling, experimentation, and analysis so results can be compared more easily. Another issue that came up was how to interpret the data. This type of sequencing can be exquisitely sensitive. However, that leads to detection of microbes at lower levels. For an academic, this is thrilling. For a company, slightly ambiguous. What happens if they get a Salmonella hit? Do they have to shut down everything or is there a level where it is of no concern? How can they make these calls when the science isn’t there to back it up? Is a good idea to implement this? I had never looked at microbiomes in this way but I could see why it was a concern.

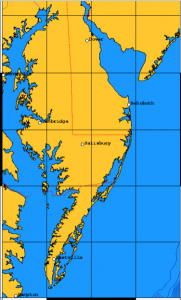

Another panel that stood out and highlighted the emerging role of microbiomes in the food world was the Delmarva panel. The Delmarva peninsula is located off of Maryland and contains Delaware and Virginia. A high intensity agriculture and tourism area, the Delmarva fences in the Chesapeake Bay and is a vacation spot for many (including this former Marylander) in the midatlantic area. Historically, tomatoes grown in the Delmarva area have been associated with Salmonella Bareilly outbreaks with a much greater frequency than those grown on the west coast. The presenters laid out a case study of the work that has gone into determining the reservoir of S. Bareilly in the Delmarva, how it acts in tomatoes, why it is seen so frequently in the Delmarva, and what can be done to mitigate outbreaks. A fascinating story unfolded that found S. Bareilly in several sources (notable stream sediment and water) and determined that it acts like a plant pathogen in tomatoes. Virulence behaviors occurred upon internalization to S. Bareilly such as pulling in the flagella to better hide from the plant by not presenting as many antigens. One of the most fascinating studies performed was the metagenomic analysis of the soil from Delmarva farms and California farms. The soil houses extremely different microbial ecosystems. Soils on the west coast contained more competitors for Salmonella spp. while the Delmarva soil contained much less. But the experiment did not end there. The FDA took it a step further and is now performing studies with strains of bacteria similar to those found in the west coast soil that could be inoculated into Delmarva soil and act as competitive inhibitors for S. Bareilly. This story amazes me. Microbiome studies and metagenomics were being used to solve a historical and far-reaching food safety problem.

But how could they do all of this? It turns out they had industry partners who were also concerned about the consistent outbreaks and wanted to help stop them. Even now, extension and outreach in the Delmarva area continues to help farmers produce safe tomatoes. That’s the real point of IAFP- to create meaningful connections to help solve food safety problems. By working together and implementing innovative technology and creative thinkers we are able to solve food safety problems of enormous magnitude. IAFP houses one of the best areas to make these connections and solve these problems. Which is why people go back every year and why I will go back.